|

| Half the fun is playing around with the miniatures.... |

One might think I’d use West End Games’ Origins-award winning miniatures rules, Star Wars Miniatures Battles, released in 1991. This was well before I joined the company as editor of the Star Wars Adventure Journal, so I don’t know much of the backstory about how this product moved from concept to release. It probably had its origins in a few elements inherent in the company at the time. West End got its start producing chit-and-board wargames, including some early titles for Star Wars; the jump to miniatures rules wasn’t a long one given the staff had experience with this kind of design and technical presentation. I’d always assumed the principle author, art director Stephen Crane, was drawn more to wargaming than roleplaying, and the comprehensive rules text and scenarios for the miniatures game reflect this (I never knew his co-author, Paul Murphy). The game itself relied on the basics from the roleplaying game – attributes, skills, die code values, Force powers, handfuls of six-sided dice – providing a solid bridge between wargamers and roleplaying gamers in a common system and setting. Yet on a recent reading I realized the game relied too heavily on system conventions from the roleplaying game, shoehorning many rules into a miniatures wargaming format that seemed to make for an overly detail-oriented simulation. This works for some people, but not for me, and certainly not for the Little Guy. I’m biased, of course, by my current attitudes as both a gamer with limited resources (time, money, focus) and one who advocates simple yet elegant game mechanics to draw newcomers into the hobby (especially kids). At first I thought I’d give the Star Wars Miniatures Battles a try on its own, but I found myself quickly overwhelmed by a time- and attention-consuming horde of attributes and skills, squad rules, movement and attack factors, squad generation points, and weapon stat minutiae. This was not a quick skirmish wargame I could easily set-up and teach my son, it was a comprehensive miniatures wargame for dedicated grognards*.

So I turned to a game designed for skirmishes, The Men Who Would Be Kings, which I’d admired for its streamlined, intuitive mechanics, fast but engaging play, and adaptability to a variety of Victorian-era conflicts. While it exemplified the differences between a well-trained military force and tribal warriors with a variety of often-inferior weapons, it still provided a framework within which I could work. I immediately set about examining the core game concepts and adjusting them to reflect the kind of action I wanted from a Star Wars skirmish.

|

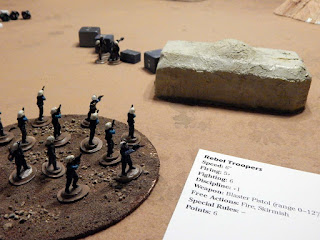

| Rebel Troopers prepare to defend their supply cache from stormtroopers. |

In all fairness I kept my first edition copy of the Star Wars Miniatures Battles rules on my desk as I typed up my notes. The old rules served as a good reference for 25mm movement rates, weapon ranges and damage, Force powers, and other factors I’d figure into my house rules. In some cases, though, I just went with intuition. While stormtrooper weapons have longer ranges than Rebel trooper blasters, they aren’t as accurate. Armor remains truly effective only in close combat. Probe droids have a host of actions, don’t have to roll leadership to take actions, and can fire or target enemy units (giving allied units a bonus to hit). Minor Jedi on the battlefield have even more options through various manifestations of Force powers, though they can only use one per turn. I’d already created my own unit reference cards for The Men Who Would Be Kings, so I ported the template and customized it for each possible Star Warsunit. I printed the reference cards, set up the wargaming table, and tested my rules interpretations with a small skirmish.

The Little Guy could barely wait to get downstairs and give the rules a try. For the first, very basic scenario I set up a small Tatooine building with some supply crates and a few desert hills. Each side had about 10 point, smaller than the half-strength forces The Men Who Would Be Kings recommends for trying out the rules; the Rebels had a squad of troopers and a poorly trained heavy repeating blaster crew, while the Imperials had a full stormtrooper squad and a half-strength scout trooper unit (using the only six scout trooper miniatures I have). The Imperials needed to retrieve the stolen supply crates from the Rebels. Unfortunately the Little Guy’s overall gaming strategy tends toward the safer side, so his units held back and hid behind the hills until Daddy got impatient and moved both his forces forward (out of cover) to engage. Obviously the Imperials slaughtered the Rebels in good order, but it gave me a chance to see how The Men Who Would Be Kings ported to Star Wars miniatures. The Little Guy seemed to grasp the basics of the rules fairly easily, though at times he seemed more interested in playing around with his figures than using them for an organized game (something I’d expect from a seven year-old anyway).

|

| Rebel troopers cover the A-wing pilot's escape. |

I’ll admit the conversion to Star Wars erased some of the Victorian nuances of The Men Who Would Be Kings. Failed leadership rolls still stymied some units; I’d used a variable system for assigning leadership values before the game, rolling 1d6 with 1=7, 2–5=6, and 6=5 as leadership values. Without variable leadership traits there were fewer bonuses and penalties arbitrarily forced on unit leaders and their performance. With all forces considered regular infantry the standard number of figures in each unit remained 12 and didn’t have cause to vary upward as with tribal infantry, ensuring most units had pretty standard strengths. The earlier games felt like blaster slug-fests, a result of fielding only a few units instead of full 24-point forces (with about four units on each side). Later games, with more complex battlefield layouts and mision parameters, had a bit more maneuvering and tension. For all their extra abilities and the ability to take any action as free, the probe droid and minor Jedi seemed underpowered; a solid attack or two from a near full-strength squad could easily take them out, even in cover. Overall, though, the rules for The Men Who Would Be Kings provided a solid framework for running Star Wars miniatures battles; I’ll continue to experiment with them and refine some of the less successfully ported concepts.

* grognard: ultra-hardcore wargamer (wargames – Advanced Squad Leader, Combat Mission, etc.). Comes from French word that means “grumbler” (www.urbandictionary.com).