“I admire anybody who finishes a work of art, no matter how awful it may be.”

— Kurt Vonnegut

I was intrigued when I discovered Geoff Engelstein writing online about a lost strategy game by renowned author Kurt Vonnegut. At first glance GHQ looked like a chess-type game using artillery and infantry, reflecting the author’s experience in northwest Europe during World War II. The design had a pleasingly mid-century aesthetic to it which felt practical for such a game. I enjoyed reading Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five years ago and have re-read it once or twice since; but I wouldn’t call myself a fan, though I’m aware of his cultural impact. The more I read about GHQ, though, the more I wanted to explore it as a gaming artifact: a game a then-fledgling author designed, tested, and tried marketing to a publishing company, to no avail, setting it aside, abandoned, for decades until, after his death, someone discovered it and finally released it to the world. Engelstein and the production team at Mars International have revived a lost treasure and provided historical context to better appreciate the game’s origins.

I love game artifacts. They’re windows into the adventure gaming hobby’s past. Even if they’re facsimiles, they bring to life a game experience otherwise lost and inaccessible. Reproductions of the Royal Game of Ur and the ancient Egyptian senet resurrect a small portion of lost civilizations we know only through the fragmentary archaeological evidence. We can read about past hobby and military wargaming like Fletcher Pratt’s Naval Wargame, Donald Featherstone's War Games Battles and Manoeuvres with Model Soldiers, and Wargames from World War II republished by the History of Wargaming Project. Adventure gaming hobby titles like Tactics II, the original Dungeons & Dragons booklets, and Ace of Aces hearken back to the exciting times when their novelty enthralled gamers...what today we might call the “new hotness.” Games from earlier times may no longer seem relevant or useful when measured by today’s standards. Yet they can still inform our current gaming activity as we look at them in the context of their unique histories and the entertainment or educational value they provided...and offer to us in the present.

Kurt Vonnegut’s GHQ provides a thoughtful package with multiple layers to explore: on the surface, a chessboard combat game based on World War II; a set of core rules with which few wargaming grognards could resist tinkering; a missing link between kriegsspielen evolved from chess and gridded wargames of today; and, at its heart, an object lesson on how our society values “art” and those making it.

GHQ the Game

Opening the GHQ box immerses one in a multifaceted experience centered on the game and its creator. Right on top of all the other components one finds an inviting bit of context: a facsimile of Vonnnegut’s Nov. 14, 1956, letter proposing the game concept to publisher Henry Saalfield of the Saalfield Game Company...as if we, discovering this box in our own time, need convincing of the game’s merit. It serves as a relevant introduction to the contents within.

The 24-page booklet beneath the facsimile letter provides “A Brief History Concerning the Creation of GHQ: General Headquarters.” Here Engelstein provides the background for his discovery of the game and Vonnegut’s development of the rules (including numerous full-page images of his original notes and manuscript). It reflects the current scholarship exploring the origins of the adventure gaming hobby we’ve seen recently, notably Jon Peterson’s Playing at the World.

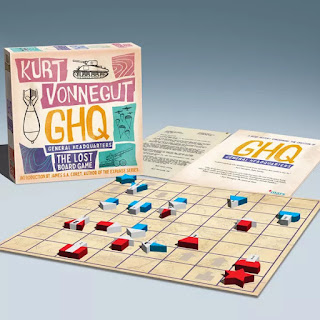

The rest of the box holds the game components: a concise rule booklet with examples and strategy notes; a folded board, eight-by-eight squares like a chessboard, but with faded background graphics reminiscent of Vonnegut’s illustration style (also evident on the box art); and a host of quality wooden pieces with red and blue highlights depicting various units (all of which fit cozily into the molded plastic box insert according to a helpful “piece storage layout” sheet). The pieces depict different military units characteristic of those fielded in WWII: the HQ, infantry, and artillery, the latter two coming in several varieties. Armored infantry moves one more space than regular infantry, just as armored artillery moves one more space than regular artillery. Each side also has two special pieces: the heavy artillery has longer range than regular or armored artillery; and airborne infantry can move from a player’s back row to any open space on the board.

To win one must capture the enemy HQ. Each player begins with three regular infantry, one regular artillery, and the HQ on the board, arrayed in opposite corners. Each turn players can activate three units, though never the same one twice. They may move a piece on the board; bring a piece from the reserves to a player’s back row; or turn an artillery piece to cover a different field of fire. Infantry captures by positioning two pieces against one enemy infantry (or the HQ) orthogonally; but enemy infantry in adjacent spaces can “engage” those infantry and prevent them from outflanking the targeted piece. Artillery captures anything within its field of fire, two or three spaces ahead of them, at the beginning of a turn. Enemy pieces cannot move into a field of fire, and must move out on their turn lest the artillery captures them. (One non-engaged infantry can capture an artillery piece.) The versatility of the airborne piece can prove very helpful, but only once...until the piece makes its way to the player’s back row again. The interplay of these pieces, their capture rules, and the choices to move or reinforce (and with which pieces) provides players with plenty of options each turn...and never enough activations to carry out planned offensives. It combines the unit variety of chess with the capture mechanics of games like hnefatafl along with concepts of multiple yet limited activations and zones of control developed by contemporary games like those created by Charles S. Roberts and Avalon Hill shortly after Vonnegut shelved GHQ.

I sat down one night with my son to give it a try. Although remembering and understanding the capabilities of different pieces took a little practice, the game moved smoothly once we started playing (and the first page of the rules offers a quick component list summarizing each piece’s functions). At first we balanced moving pieces forward and bringing in reserves; notably the heavy artillery and airborne infantry came out in the first turns given their powerful abilities. Once reserve pieces arrive, players juggle their offensive moves while defending against possible enemy attacks next turn. It sometimes became overwhelming with so many pieces with varying capabilities on the board. I found myself so focused on my own plans that I often overlooked threats posed by enemy pieces nearby. We both had a few “gotcha” moves in the game, taking advantage of oversights to capture enemy pieces. It played fairly quickly, about 20 minutes after we’d gone over the rules. At first we seemed pretty balanced in how many pieces we each lost; but toward the end it descended into a drawn-out end game when it became clear one player had barely enough pieces to win. Overall, however, I felt it abstracted the kind of broad combat action Vonnegut experienced during WWII, to the point where it might help, as much as any game, in educating players on the interplay between infantry and artillery on a battlefield.

Tinkering & Evolution

The basic concepts behind movement and capture — by outflanking infantry or bombarding artillery — tempt the seasoned wargame grognard to tinker with the systems. New players naturally spend time learning the interplay among the different pieces. The game certainly has enough tactical depth to sustain multiple plays and varied strategies. But adventure gaming enthusiasts can rarely resist adjusting rules, inserting their own modifications, and otherwise custom-fitting a game to their particular play styles. The concise rules in GHQ provide a solid foundation for alterations. How might one represent units from other eras using the same core game capture concepts? Could one model historical battles with this game? What role might terrain play on the otherwise clear chessboard arrangement? Would hills and forests block artillery or slow armored units? And could we mark terrain on the board with tiles covering relevant spaces?

My mind starts racing with possibilities. Could one simulate battles from earlier times using the same capture mechanics? Infantry could operate the same, as could artillery, though far more limited than the variety GHQ presents. Cavalry could function as armored infantry in terms of moving two spaces rather than one. Heavy, light, and horse artillery could work in similar fashion to units in GHQ. I’d even be tempted to try setting terrain to block or slow units. (Some games, like The Portable Wargame mentioned below, accomplish this quite well already, though, using more gamey mechanics involving dice and more traditional wargame modifiers.)

GHQ also fills an interesting link in the progression of wargame design. Just as kriegsspielen initially evolved from modifying chess on a grid with adjustable terrain and contemporary units (then moved to a more free-form map), GHQ embraces its chess ancestry with an effective yet still abstracted representation of period combat. “Gridded” maps dominated the board wargame market Avalon Hill, SPI, and others pioneered in the earlier days of the hobby wargame industry. Their sprawling map boards influenced the 21st century board game market, with monstrous “table hogs” spread out across kitchen and dining room tables...and even custom game tables. Yet GHQ hearkens back to a time when one could experience a quality game without taking up so much space. The chessboard playing field and the variety of pieces provide a challenging tactical experience despite their seeming simplicity. This return to basics — and small footprints — has seen a revival in more recent miniature wargaming rules like Bob Cordery’s The Portable Wargame and Gridded Naval Wargames (along with those from other designers). These and games like GHQ prove one can play out entertaining, meaningful battle games on a play surface as compact as a chessboard.

The Creator’s Struggle

The package we get with GHQ also highlights the creative struggle of a designer trying to elevate his game beyond his own family’s enjoyment; to sell it to a publishing company and bring in desperately needed income. Vonnegut took considerable time to design, craft, playtest, and draft rules for GHQ at a point in his life when he took various jobs to support his family. Creativity for this game and his writing occurred in what time he could find when he wasn’t struggling for survival. The notes and letters in the “brief history” of the game offer a glimpse into his creative process...and the challenges and disappointments he faced. It is a game born out of a specific time and situation from a unique and talented individual.

One might find a degree of irony that a person later well-known for his anti-war sentiments had once designed a wargame. Having survived the Battle of the Bulge, Vonnegut had a direct connection to the elements of WWII combat. He may have designed and tested the game as a way to address the traumatic stress haunting him much as he later used his fiction to explore his disturbing experiences and their repercussions on everyday civilian life. Perhaps he found some solace channeling his own trauma into something with potentially positive and playful results; certainly it was a means to find some source of income, however unsteady.

Vonnegut’s process in designing and trying to sell the game illustrate similar practices and challenges game designers face today. Although he may have exaggerated claiming “I have played the game about a thousand times,” he certainly spent a good deal of time playtesting the game with his son and the neighborhood kids, enough to iron out design issues to make it work “like a dollar watch.”

The game’s journey from designer to publisher to almost-forgotten archive box shows just how much selling a game involves talent, opportunity, fortuitous circumstance, and sheer luck...or lack thereof. Perhaps Vonnegut tried designing and selling a board game because his neighbor was a cousin of Henry Saalfield of the Saalfield Game Company, the toy and game department of the Saalfield Publishing Company of Akron, OH. After a year the company finally rejected the innovative game (after Vonnegut apparently submitted a copy); ironic considering Saalfield gained its fame as the largest children's book publisher in the world at the time...by accepting an unsolicited story pitch about a goat from a first-time author. Nobody has uncovered evidence of Vonnegut trying to market the game to larger board game companies of the time like Milton Bradley or Parker Brothers (both located in Massachusetts, where Vonnegut lived). Vonnegut’s experience reflects the long, tenuous, and mostly unsuccessful process of connecting a creator with a company willing to take a risk to produce and profit from their creation.

GHQ might not satisfy every modern gamer’s tastes. I don’t expect “artifact” games to measure up to today’s extremely high standards for board game complexity, high production value, and strategic nuance, all the bells and whistles we’ve come to expect in our current gaming renaissance. Yet GHQ holds its own, using basic concepts of movement and capture, an interesting reserve system, that pesky airborne unit, and the creative strategies of two players deploying their varied forces on the chessboard battlefield. Like any game, GHQ won’t entertain everyone, but it has broad appeal on multiple fronts: anyone interested in abstracted wargames of WWII; fans of Vonnegut seeking to explore another aspect of his creativity; people who like gridded wargames on chessboards; and folks, like me, who enjoy bits of lost literary and ludic history, game artifacts from another time that might broaden our perspective and give us pause to reflect on where the hobby’s been...and where we’re going.

“The arts are not a way to make a living. They are a very human way of making life more bearable. Practicing an art, no matter how well or badly, is a way to make your soul grow, for heaven’s sake.”

— Kurt Vonnegut

Thanks for your kind comments about my rules. I feel quite humbled to be mentioned in a post about a game devised by one of my favourite authors.

ReplyDeleteAll the best,

Bob

Bob, your rules carry on an oft-overlooked tradition of wargames on chessboards...even if my own staged efforts tend toward the larger gridded wargames....

Delete