“That the future may learn from the past.”

– Colonial Williamsburg mission

|

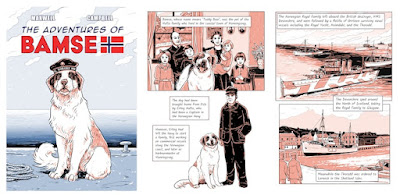

Bamse samples: artwork by Julie Campbell and writing by Colin Maxwell. |

I enjoy learning about various periods in history, from the broad picture to the smaller, more personal stories and everything in between. My engagement spans the vast landscape of media, from non-fiction books and documentaries to the more embellished films, historical novels, and, of course, games. And even comic books. So when I discovered Colin Maxwell of Maximized Comics Kickstarting another history based comic book, The Adventures of Bamse, I didn’t hesitate to back it. I’d previously backed and enjoyed his earlier true-war stories, Raid on the Forth and Flight of the Eagle, two relatively obscure episodes from World War II (well, “relatively obscure” to those of us who don’t live in Scotland...). Both draw on events related to his own local history, so I couldn’t resist supporting publication of the story of “the dog that became the mascot of the Free Norwegian Forces during the Second World War.” (At the moment the project still needs funding in the final days of the campaign – which offers the chance to also get the previous two comics, all well worth the price even considering shipping from the UK to the US.) These comics remind me how history consists of many stories great and small, far-reaching in scope yet also personal. Humans have loved storytelling throughout time...and history is our own epic tale, a larger-than-life story we can also draw upon for our games, whether historical wargames, board games, or even roleplaying games.

Society has long valued storytellers, from the earliest priests who recorded myths on papyrus and clay tablets to poetic scops weaving tales around the campfire, troubadours at court singing of heroic deeds, and playwrights inspiring actors on stage. Modern culture revels in popular storytelling: radio, television, film, novels, comics, streaming media, and even the adventure gaming hobby. Each of us indulges in storytelling, too; when we get home from work or gather with friends we share those fleeting anecdotes from our daily lives involving our own setting, antagonists, and conflicts. Good stories inform and entertain. Every story invites us to learn something about ourselves and our world.

History represents the confluence of people and events that led us to our present moment in time. It has, in various ways, contributed to our current lives: the technology we enjoy, our nationalities, our beliefs and values, our family backgrounds – a reflection of ourselves, our own story – and where it’s all leading us. History shares many elements with stories: characters, conflicts, setting, and escalating events all converging on climaxes that lead to new misadventures. But unlike fiction, these stories come from our own real past and don’t always play out to a happy ending.

History can inform and teach; our emotional connection to its stories can linger in our minds longer than mere information. Certainly modern American public education – with its emphasis on regurgitating facts, names, and dates on a standardized test – could benefit from focusing on relevant stories within the context of a historical period or issue. The facts and dates and names all matter, of course, but have no meaning without context...the framework of the history in which they all play some role. Stories invite us to explore the past by putting ourselves briefly in the shoes of those who came before us. Our involvement often takes the passive form of reader/viewer, with the option to further reflect on and explore the issues presented (a subject I’ve discussed before). The invitation waits for us to take it, to invest the time, effort, and open mindedness to critically explore how the characters, conflicts, setting, and escalating events of a historical period come together to form a story from which we might learn something about ourselves and our world, past and present.

Our consumption of stories – historical or otherwise – tends toward passive forms. We read books, watch movies, absorb knowledge fed to us in classrooms. It’s still up to us to take the effort to immerse ourselves in the story and form that empathetic bond with the material. It doesn’t usually take much effort, especially for excellently told stories that enthrall us. But our involvement remains passive. Games, however, invite us into a safe-to-fail space where we can further explore stories by becoming involved through play. We take an active role in the storytelling. Roleplaying games represent perhaps the best example, where players assume roles and pursue goals in a setting, with the gamemaster presenting background elements and adversaries; sometimes this occurs in the “theater of the mind,” but it can also involve maps, figures, and other accessories to help visualize the action. Other forms of games involve us in storytelling to varying degrees. Perhaps we command a mighty Star Destroyer and TIE fighter squadrons in Star Wars: Armada. We battle other kaiju in King of Tokyo as we amass an astounding array of powers. We feel the crew’s terror as we struggle to escape the xenomorph in Alien: Fate of the Nostromo. We participate directly in the stories unfolding on the game board or around the gaming table.

Just as other games immerse us in stories, historical games, however abstracted or painstakingly detailed, invite us to actively participate in experiencing stories from our past firsthand. History forms the cornerstone of board and miniature wargaming. Most games seek to simulate to some degree actual engagements, though some encourage players to explore smaller actions that could have happened. These games invite us to actively play with historical elements as entertainment, leaving each individual player to familiarize themselves with the context and further explore the period if they wish. History games offer an opportunity not simply to play with history, but to consider some of its implications at various levels. What’s it like to pilot dive bombers during the attack on Pearl Harbor? What happens to that unit of infantry if I send it into a a close-combat bayonet charge? Do I admit defeat and retreat or do I press the attack and further deplete my forces? What’s my country’s motivation in sending troops armed with rifles and cannon to suppress a revolt by indigenous people armed with swords, spears, and bows? I’ve explored touchy issues about “playing with history” several times before, including the primary one about playing the “bad guys.” We can simply play historical games for entertainment, but it invites us to further examine the period and take a closer look at elements driving these historical stories. Maxwell’s Maximized Comics stories have already inspired my gaming. I’ve collected enough Spitfires and Junkers 88 bombers for Wings of Glory to run a game simulating the mission in Raid on the Forth (for one of our summertime father-son game sessions). Flight of the Eagle might inspire some other historical and solitaire game design dealing with the theme of where to go when one loses one’s country. Along with The Adventures of Bamse they invite people who’ve never heard of them to immerse themselves in compelling stories and interesting local history – small but important stories within the vast scope of World War II – and perhaps explore other tales of our past beyond the known and familiar. These might seem like distant stories about people different from us living in a different time; but they reflect aspects of human nature. For a short while we put ourselves in their shoes, sometimes passively experiencing media, other times exploring their stories more directly playing games. Whether we identify with them or reject them, they may influence, even in small way, the stories of our own lives.

“That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most important of all the lessons of history.”

– Aldous Huxley

No comments:

Post a Comment

We welcome civil discussion and polite engagement. We reserve the right to remove comments that do not respect others in this regard.