These kinds of board wargames – some might call them “battle games” – stuff a host of high production value components in a box, with a card deck (or decks) serving the central mechanic governing movement or combat or both. They’re cousins of the current spate of board games (“current” being 21st century...) and much more manageable descendants of chit-and-board wargames without all the dense rules, fussy combat resolution tables, and tiny cardboard chits. Such games include titles in the Commands and Colors series by Richard Borg (Napoleonics, Ancients, Battle Cry, and Memoir ’44), Worthington’s Hold: The Line American Revolution, and Nexus’ colossal Battles of Napoleon; games in my collection, most of which I’ve played. They use boards with hexagonal grids, cardstock terrain to arrange for different scenarios, and card decks giving players options on units to move and attack. Those that don’t use plastic miniatures show formations as wooden blocks with stickers of the appropriate units. They’re not overly complex and about as close to an attractive introduction to wargaming as we’re liable to get.

Manoeuvre

Designer Jeff Horger’s Manoevre musters two players to face off on an early 19th century battlefield. The box packs a satisfying array of components: color rulebook, two player reference cards, 24 geomorphic card map sections, four each of d6, d8, and d10, and eight unit counters and a 60-card deck for each nationality (Britain, France, Prussia, America, Turkey, Russia, Austria, and Spain). Each deck includes orders for specific units and a host of other helpful cards to play in enhancing movement/attacks, interrupting enemy actions, and reinforcing units. Unit counters (about an inch square) include flag and soldier graphics and a strength value (with a reduced strength on the back for units taking casualties).Manoeuvre includes some intriguing elements. The board consists of four of those 24 geomorphic card map sections: each one displays a four-by-four grid and fills squares with various terrain (lakes, hills, forests, towns, marshes). Players randomly draw four and arrange them to form a battlefield, ensuring they’re fighting over different terrain every game on a gridded space equivalent to a chess board. Every army has eight units, typically two cavalry and six infantry, though with different strengths and, incorporated in the cards, different combat abilities. Players maintain four-card hands enabling them to attack with units specified or take additional battlefield actions. Each side gets to move one unit each turn and play cards to initiate attacks with units in range. This encouraged some interesting player choice during play. In several instances I had strong units in place but no cards to order them to attack! Unit cards can also serve to bolster defense; do I save this unit card for a future assault or use it now to keep that unit from damage or destruction? Do I discard some cards to cycle through my deck hoping for better cards? Because if I do, I rush the game toward its conclusion. The game ends when one side loses five units or when a player runs out of cards; in this case, each army determines how many spaces on the enemy side of the board they control, the winner holding the most enemy territory.

I found numerous elements to enjoy in Manoeuvre. The graphic presentation of cards, counters, and board worked for me. Arranging different geomorphic terrain tiles each game provided completely new battlefields demanding different tactics. Along with the eight different armies, the game offers excellent replay value if you enjoy its other aspects. The card system forced me to make careful choices on several levels; though when I started drawing cards for eliminated units later in the game I felt frustrated (and quickly discarded them when I could to gain new cards). I played several games against myself solitaire, commanding the British and French, giving each side my best effort; every game ended with one side taking its fifth loss and, as Wellington would have said, each contest was a “close-run thing” right to the end, as in any good game.

(I found a reasonably priced used copy at Noble Knight Games, since Manoeuvre is currently out of print, though GMT has a campaign to fund a reprint.)

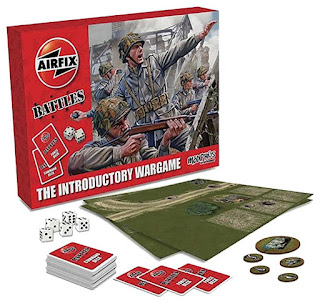

Airfix Battles

Billed as “The Introductory Wargame,” Airfix Battles provides a card-driven combat system one might use with the company’s 1:72-scale World War II miniatures. Though it doesn’t include figures, the game comes with top-down counters of soldiers, vehicles, and terrain to play all the scenarios. The box packs a host of nice-looking components: two double-sided, full-color 11x17 maps of the Normandy countryside with a five-by-seven square grid over them, 10 six-sided dice, cardstock counters, a deck of command cards (from which both players draw), a deck of “force” cards, half Axis, half Allies, depicting various units in game terms, and a full-color rulebook and missions book.The rulebook walks readers through the basics of play – unit abilities, movement and attacks by card play, morale, assaults, etc. – it directs them to relevant scenarios from the missions book to play with and reinforce those rules. So far I’ve only played the first scenario, two opposing infantry squads with a commander and some veterans, mostly using the included solitaire rules and once with me earnestly playing both sides (more on the solo rules below). Beginners can appreciate having a top-down representation of everything on the field: the terrain, ruins, individual soldiers, vehicles (though the “rough terrain” chits didn’t seem quite right). The rules encourage players to use their own miniatures (Airfix or otherwise) while noting it’s not necessary to enjoy the game as presented. But infantry units consisting of five or ten individual soldiers soon became tedious. After one game pushing around crowds of penny-sized soldier counters I broke out some painted Flames of War miniatures on bases, with each base representing five soldiers, and games moved much faster without all the fuss.

Like Manoeuvre, Airfix Battles relies on players choosing actions from command cards to move and attack with units. Commanders on each side limit the hand size and cards played each turn (something one can change when recruiting their own forces in more advanced rules). While many cards gave units advantages based on various situations, they also limit the tactics one can pursue. Since both sides draw from the deck, each must use the strengths of their individual units (different kinds of attacks, some advantages) and the benefits of cover on the battlefield. Once I brought my based miniatures onto the board the game moved quickly; the other side of each soldier token shows a blast marker, useful in keeping track of strength losses for each unit. Bold moves proved powerful at the start, before units (and their firepower) degraded by taking damage. Most attacks roll one die per soldier involved, though grenades, for instance, have a chance to hit each soldier in a space. The gridded battlefield helped judge range and movement; with the top-down graphics it still had the look of realistic terrain in a minis game.One of the main reasons I bought Airfix Battles was to try the solitaire rules. Card-driven games can often use that mechanic in randomizing opponent actions and responses. On first glance these solo rules accomplish that. But in play I noticed several issues. Where the number of cards played each turn was limited by a commander’s value (in this case, two cards), the “bot” opponent kept drawing cards until all units acted. This disparity led me to defeat in every game. The solo rules didn’t seem to take into account bot-controlled units that were pinned or in retreat (unless I completely missed those somewhere), providing no option for morale rolls to rally those units back to operational status. Despite instructions on the cards and a table to interpret most card effects in solo mode, I often found myself opting for the default orders when conditions didn’t match those in the solo instructions. It was far easier and more satisfying playing against myself as usual, evaluating my options and using the best possible strategies for each side based on the battlefield situation.

(I bought my copy from Amazon at a reduced price for a dinged box; it wasn’t that badly damaged and the components were fine.)

Love for Battle Games

Both games reminded me of the how much I like battle games. While they don’t offer the versatility of miniature wargaming rules, they often provide a complete package for gaming in a historical period, usually with less complex rules. Aside from high-quality components, such games provide players with everything needed to learn the game and play numerous sessions with different scenarios. I wouldn’t consider Manoeuvre and Airfix Battles “introductory” games on their own, though. They provide a good start, but both could use an experienced adult to introduce them to younger players unfamiliar with wargaming concepts. But game mechanics and reminders on cards and reference sheets speed play once newcomers carefully digest the rules. Such games have excellent replay value, whether choosing different armies and altering terrain or playing through various historical scenarios. The card mechanics limit player choice – avoiding the often overwhelming situation of not quite knowing what units to move where – and in a sense force players to allocate card “resources” in the best way possible at the time, making tough decisions in pursuing an overall strategy.

Where some might see limitations in these games I see opportunity. Certainly I could craft larger or more elaborate versions of each game to take into account custom terrain and miniatures. I’ve found this approach works well when trying to introduce wargames to newcomers in settings like museums and libraries, where casual observers might find the visual presentation attractive enough to play. Battles games often come with a host of historical scenarios to fight, but they also lend themselves to gamers creating their own situations. For instance, I’d love to use Airfix Battles for World War II battles in the Pacific or North African theater; while the existing cards cover American and German forces in western Europe, I could use them to represent different forces or create my own (with a little more effort). Although Manoeuvre doesn’t offer historical scenarios for specific engagements, one could peruse the existing tiles (or make their own) to represent the terrain for notable early 19th century battles.

Both Manoeuvre and Airfix Battles add to the existing repertoire of battle games across different historical periods. As usual one’s mileage may vary based on preferences for mechanics, graphic presentation, and other subjective criteria; but overall they’re solid and enjoyable games with high replay value.

You might like to try any of Mike Lambo's books. I've read nothing but good things about them, but nothing by someone I'd trust (I just haven't followed them previously, nothing about them personally).

ReplyDeleteThey seem like something you'd be interested in.

I've seen Mike Lambo's books on Amazon; I'm always tempted. Guess I'll have to find one for a period I like and give it a go. Thanks for the recommendation.

ReplyDelete